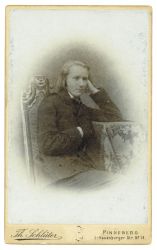

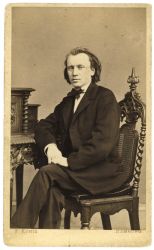

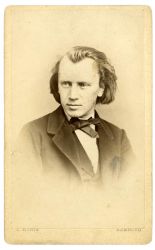

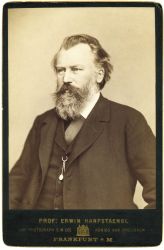

Johannes Brahms

A Brief Biography

Johannes Brahms was one of the most influential composers of the nineteenth century. Apart from an opera, the Hamburg-born composer created exemplary works in all musical genres: orchestral music (four symphonies, concertos), chamber music, piano music, oratorios and choral music (Ein deutsches Requiem) and a very extensive body of songs.

Individual compositions already met with great success during the composer’s lifetime. His Ungarische Tänze WoO 1 in particular enjoyed great popularity, although several conflicts broke out over the authorship of the melodies during the 1870s. One of the composer’s most prominent pieces was the lullaby »Guten Abend, gut Nacht«, which achieved the status of a proper folk song in the popular reception. Goodbye Again, the film adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s novel Aimez-vous Brahms?, played a key role in the popularization of the composer in the age of the mass media: The third movement (Poco allegretto) of his Symphony No. 3, op. 90, became a classic of film music.

Johannes Brahms was born in Hamburg on 7 May 1833. A key event in the young composer’s life and decisive for his later development was his encounter with the couple Robert and Clara Schumann in the fall of 1853. In his famous essay »New Paths«, Schumann celebrated the twenty-year-old composer enthusiastically, even before he had even published a single note. »Everything about him seems to suggest to us: here is someone with a calling.« Schumann praised the »ingenious playing« of the young pianist, who could turn the piano into an »orchestra of lamenting and jubilant voices«. »They were sonatas, or rather, veiled symphonies«, Schumann continued, then predicting: »If he waves his magic wand where the powers of the masses lend him their force in the chorus and orchestra, even more wonderful glimpses into the mysteries of the spiritual world await us.« But the impact of Schumann’s enthusiasm was not entirely positive. The article was also a burden on the young composer: for the rest of his life, Brahms would be measured according to these prophetic words.

For Brahms, Ein deutsches Requiem marked his breakthrough as a recognized composer. At the Bremen premiere of this work, which was then still lacking the fifth movement, Clara Schumann recalled her husband’s article: »Seeing Johannes standing there with the baton in hand, I had to think over and over of my dear Robert’s prophecy, ›let him wave his magic wand and have his way with chorus and orchestra‹ that today came to fulfillment.«

In 1869, Brahms began to think about moving to Vienna permanently. At the end of December 1871, he moved to a rented apartment at Karlsgasse 4 that he kept until his death. Tellingly, Brahms always had a bust of Beethoven »breathing down his neck« when sitting at the piano. Even in the early 1870s, the composer said to his friend the conductor Hermann Levi that he »would never compose a symphony! You have no idea what it is like to hear a giant like Beethoven always marching behind you! « But with his Haydn-Variationen from 1873, Brahms achieved the full control over the orchestra and the path towards his first symphony now lay before him. The First Symphony, a symphony that is decidedly focused around the »finale«, demonstratively engaged with Beethoven, and yet the famous nickname »Beethoven’s Tenth« (Hans von Bülow) is only partially fitting. That the C major theme of the final movement openly corresponds with Beethoven’s »Ode to Joy« theme from his Ninth Symphony is something that »any jackass« could hear, in the words of the composer.

Whether Brahms could claim to be Beethoven’s legitimate heir was a question that played a main role in the nineteenth century rift between progressives and the conservatives. The opposition between Brahms and the progressive »new Germans«, against whom Brahms already signed a manifesto in 1860, was based on a fundamentally different understanding of music history. Liszt and Wagner had dedicated themselves to the »music of the future«: they wanted to drive the development of music forward with the symphonic poem and the musical drama. Brahms’ goal in contrast, to use a favorite expression of his, was to create an »enduring music« that could stand the test of time and historical change due to its inherent qualities. He especially favoured chamber music that introverts itself, while at the same time orienting itself towards the »laws of pure music« only.

During the last two decades of his life, Brahms was a leading figure on the international music stage, widely admired and honored as a pianist, conductor, and composer. He was regaled with numerous awards and honors, which Brahms commented on subtly: »If a pretty melody comes to mind, I‘d prefer that to a Leopold medal. « The University of Breslau awarded him an honorary doctorate, and the city of Hamburg made him an honorary citizen, a rare honor that had been bestowed upon the likes of Bismarck and Moltke. Already in 1881, Clara Schumann wrote in her diary that »she was very pleased« to see »Brahms so well-acknowledged«; she continued to say that he is celebrating triumphs virtually unknown by any previous composer. Brahms died in Vienna on April 3, 1897.

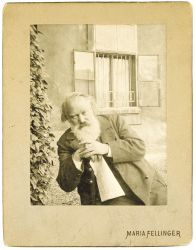

Soon after his death, the need grew for a public honouring of the composer, lasting over the ages. Memorials took very different forms: there are the actual monuments, statues and busts that were erected in his honour. The most artistically significant can be found in the Thuringian residence city of Meiningen, in his hometown of Hamburg, and in the place of his most intense creative work, Vienna. But the large, several-volume Brahms’ biography by Max Kalbeck — the first volume was published in 1904, was equally monumental, as was the first Complete Edition of his Works, published in 1927/27 with 26 volumes.

Some of these monuments have, over the years, come to seem somewhat spurious: the monument by Max Klinger located at Hamburg’s Musikhalle shows a towering Brahms surrounded by muses and geniuses, a human being that, although made of Carrara marble, seems to grow to supernatural dimensions. Regardless of the aesthetic repute of this impressive work: today we can hardly percieve the composer as seen through the eyes of Klinger. The Brahms’ bust by Prague sculptor Milan Knobloch that entered the Walhalla near Regensburg in 2000 shows a young Brahms without a beard in a concious contrast to earlier depictions.

The image of Brahms that Max Kalbeck sketched out over hundreds of pages in his apologetic biography has also been corrected and complemented on many points by later research. And in Kiel under the patronage of the Konferenz der deutschen Akademien der Wissenschaften, a new complete edition of Brahms’ works is being prepared, based on much more extensive sources and new methods of editorial practice. The source basis for this edition could be expanded not least due to extensive new acquisitions of the Brahms-Institut.

[Wolfgang Sandberger]